3 on the 21st: When the Gut Speaks, the Brain Listens

- neurosutton

- Jan 21

- 2 min read

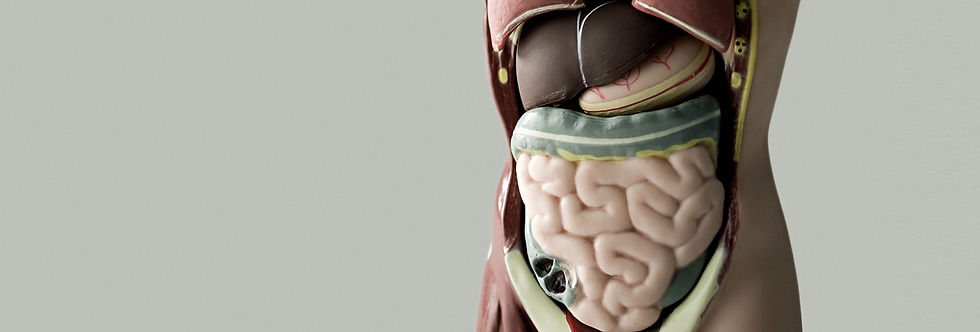

Parents often notice that when something’s off in their child’s belly, everything else—sleep, focus, even mood—can fluctuate. That’s not coincidence; it’s physiology. The gut and brain are in constant dialogue through the vagus nerve and a web of hormonal and inflammatory signals (Mayer et al., 2015). In children with Down syndrome, this gut–brain loop is especially sensitive, meaning disruptions in digestion or feeding reverberate through attention, mood, and learning.

In this 3 on the 21st edition, we’re unpacking three of the most common co-occurring GI conditions in DS and what they mean for brain development.

1. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

When acid or stomach contents flow back into the esophagus, it can cause micro-aspiration, pain, and frequent night waking. Each of these interrupts the brain’s fundamental work of growth and learning. Sleep fragmentation, in particular, limits memory consolidation and reduces neuroplasticity—two keys for language and motor development (Marcus et al., 2022).

A burning or “spitty” gut makes it hard to sleep, eat, and focus. Addressing reflux—through diet, positioning, or medication—often brings surprising improvements not only in comfort but in attention and mood. Treat the reflux, and sometimes you see a child rejoin the world of curiosity.

2. Constipation and Motility Disorders

Constipation is not just about delayed stooling—it’s about discomfort, inflammation, and disrupted gut–brain chemical signaling. The enteric nervous system communicates with the brain via neurotransmitters like serotonin; when the gut moves slowly, those signals shift (Müller et al., 2021). Chronic discomfort can elevate stress hormones and reduce self-regulation capacity, making behaviors look “challenging” when the real issue is trapped stool and belly pressure.

When the gut is stuck, everything feels more difficult. Treating constipation can lighten mood, reduce irritability, and open space for learning.

3. Feeding and Oral-Motor Discoordination

Eating is one of the brain’s most multisensory workouts. Chewing, swallowing, and coordinating breathing engage motor cortex, brainstem, and sensory integration networks all at once. Many children with Down syndrome have low oral tone or delayed chewing skills, which limit exposure to textures, tastes, and the social world of meals (Arvedson, 2019).

Feeding therapy strengthens safety and skill—building oral-motor coordination but also neural connections for speech and social engagement. In this way, "feeding” is developmental nutrition: every safe swallow is practice for communication and emotional connection.

References

Adams, D. (2020). Neurodevelopment in Down syndrome: The influence of systemic health factors. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 62(4), 486–494.

Arvedson, J. C. (2019). Assessment of pediatric dysphagia and feeding disorders: Clinical and instrumental approaches. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 25(3), 140–152.

Marcus, C. L., et al. (2022). Sleep, breathing, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with Down syndrome. Pediatric Sleep Medicine Annual Review, 18(1), 33–45.

Mayer, E. A., Knight, R., Mazmanian, S. K., Cryan, J. F., & Tillisch, K. (2015). Gut microbes and the brain: Paradigm shift in neuroscience. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(41), 13860–13867.

Müller, P. A., Schneeberger, M., Matheis, F., & García-Cáceres, C. (2021). The gut–brain axis in health and disease: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic approaches. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(9), 527–544.

Comments